Proximity Search

9 min read • Keoni Garner

A How-To on the different methods for solving proximity search.

I use MacOS and only MacOS so all examples will be for MacOS.

Table of contents

Hypothetical

You are a software engineer at a startup with access to your customer’s addresses. You have been asked to evaluate a solution to a product ask: Searching for other addresses near an address qualifier.

I’ll spend some time pulling apart the different levels of product complexity and then providing some instructions on how to solve these with minimal effort - a goal for which all engineers should strive.

The Problem

As with most requests from customers, clients, or product, the scope can be nebulous and expand quickly. What was presumably a single ticket can easily expand to entire feature lanes so it’s important (especially as a startup engineer) to cut scope where possible.

This ask is no exception. For the intents of this situation though, let’s assume we have a decently-scoped product spec.

- Buffer Search: given an address qualifier and a proximity bound, find all customer addresses within the region + the proximity bound (“as the crow flies”)

- Radius Search: given an address qualifier and a radius, find all customer addresses within the radius from the centroid of the region

- Assume US addresses only

- REQUIRED: For regions whose granularity is greater than or equal to a 3-digit zip code, use Radius Search

- NICE TO HAVE: For regions whose granularity is less than a 3-digit zip code (e.g.. county or state), use Buffer Search.

- NICE TO HAVE: Accuracy 97% or higher

- NICE TO HAVE: Buffer search on all address qualifiers:

- Full Address

- City/State

- 3-digit zip

- 5-digit zip

- 9-digit zip

- County

- State

This is just an example of a simple spec for this feature. YMMV.

With so many Nice-to-Haves, how can we properly descope so we don’t overwhelm the implementing engineer(s)? I like to present different approaches with vastly different timelines and pros/cons and let someone else decide on the approach. In this way, the decider can make an educated decision and keep “realistic” expectations.

The Solution(s)

I’m going to present two solutions in this section. Each will have its own merits and drawbacks in addition to a reasonable time estimate for a single software engineer to complete each solution.

Solution 1: Scrappy Doo

In true startup-fashion, let’s evaluate how we might add this feature with as little infrastructure as possible.

First thing you should know is that the US government releases the polygons for each of these regions we might need every time they change. It’s completely free and open to use if you know how to use it.

Second is that this solution will assume ONLY RADIUS SEARCH since it’s the only required ask.

Third is that we can do a very rudimentary distance calculation between two Cartesian points via the Haversine equation.

With these in mind, let’s get into the solution.

drum roll 🥁

🎉 flat files! 🎉

That’s right! Let’s pre-process the geometry files and create a mapping of qualifier: centroid to give us our centroid for the calculation.

If you later want to seed your database with these files, you can fairly easily do so.

Step 1: Download the file(s)

We will need a file for each “layer” we want to support (e.g. ZCTA520 for both 3 and 5 digit zip codes)

Convenience script to do this ✨automatically ✨:

### Downloading Shapefiles ###

# Specify the URLs of the shapefiles you want to download

# Zip Code tabulation areas (ZCTA) for US

us_zipcodes_url="https://www2.census.gov/geo/tiger/TIGER2022/ZCTA520/tl_2022_us_zcta520.zip"

# Directory to save downloaded shapefiles

output_dir="./shapefiles"

# Create output directory if it doesn't exist

mkdir -p "$output_dir"

# Function to download a shapefile from a URL, extract the zip file, then delete the zip file

download_shapefile() {

local url="$1"

local output_filename="$2"

curl --continue-at - --progress-bar -o "$output_filename" "$url"

unzip -o "$output_filename" -d "${output_filename%.zip}"

}

# Download US ZIP codes shapefile

us_zipcodes_filename="$output_dir/tl_rd22_us_zcta520.zip"

download_shapefile "$us_zipcodes_url" "$us_zipcodes_filename"

Step 2: Process the shapefile(s)

Utilizing a very well-maintained Python library (geopandas), we can very cleanly parse a shapefile directly in to a CSV that will represent a relatively static database table. You can use this to seed a database table so you can quickly look up a centroid and possibly offload all of the work to the database.

pip install geopandas

import geopandas as gpd

def extract_centroids_from_shapefile(input_shapefile, output_csv):

# Load the shapefile into a GeoDataFrame

gdf = gpd.read_file(input_shapefile)

# Calculate centroids

gdf['latitude'] = gdf['geometry'].centroid.y

gdf['longitude'] = gdf['geometry'].centroid.x

# Extract relevant columns and write to CSV

gdf[['ZCTA5CE10', 'latitude', 'longitude']].rename(columns={'ZCTA5CE10': 'postal code'}).to_csv(output_csv, index=False)

# Example usage assuming you've used the bash script above

extract_centroids_from_shapefile("./shapefiles/tl_rd22_us_zcta520/tl_rd22_us_zcta520.shp", "output.csv")

Each layer will have its own mapping, so there may be better ways to do this and richer logic paths to accommodate them in one script. This is just one example.

Which should result in a mapping file like:

| postal code | latitude | longitude |

|---|---|---|

| 93301 | 35.3843365 | -119.0205616 |

| 93302 | 35.5522 | -118.9188 |

| … |

Repeat this for each file/layer/address qualifier that you need to support.

And there you have it! A file you can now use to seed your database with.

I will not be going into detail on how to seed the file into your database as it will vary widely based on the tech stack you’ve chosen. There are plenty of resources for this step though on the internet.

Step 3: Use the [data] Luke

Assuming you have a customer_addresses table with latitude and longitude columns, a query for the radius search (in kilometers) could look like this:

SELECT id, (

6371 *

acos(

cos(

radians({centroid_latitude})

) *

cos(

radians(latitude)

) *

cos(

radians(longitude) -

radians({centroid_longitude})

) +

sin(

radians({centroid_latitude})

) *

sin(

radians(latitude)

)

)

) AS distance

FROM customer_addresses

HAVING distance < {radius_in_km}

ORDER BY distance;

Be sure to replace {centroid_latitude}, {centroid_longitude}, and {radius_in_km} with the values you need for your query.

That’s pretty much it. Radius Search in just a few steps.

Step 4: Optimization (Optional)

Note that the Haversine calculation must be run for each record in the database. If your database is millions of records large, this will become problematic. The easiest way to filter this down is to do basic geometry.

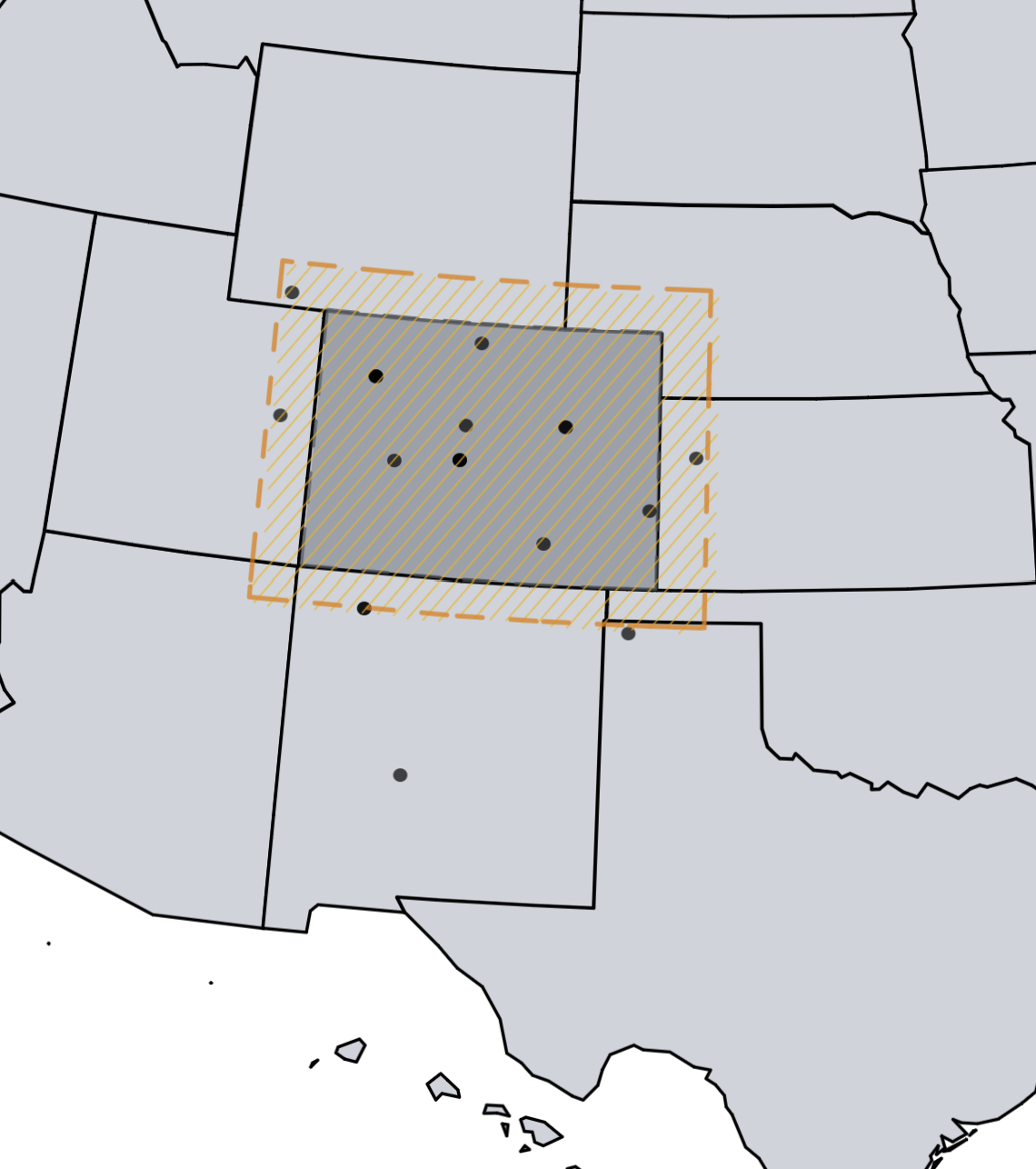

If Haversine can be viewed as a circle around a given point with a supplied radius, we can also use that radius to overlay a “bounding box” around the circle such that the sides of the bounding box are equal to the diameter of the circle. In this way, we can do a very rudimentary query to filter our results first before calculating the Haversine distance:

SELECT *

FROM customer_addresses

WHERE

latitude BETWEEN (centroid_latitude + radius) AND (centroid_latitude - radius)

AND

longitude BETWEEN (centroid_longitude + radius) AND

(centroid_longitude - radius)

If you have tolerance for inaccuracy, you might feel comfortable with just this bounding box search which is perfectly reasonable too!

Estimate

Time estimate: 1-2 weeks

Realistically, this could just be a single sprint’s worth of work considering differing PR processes, testing and validation, etc. I would be surprised if an engineer took longer than 2 weeks to do this but there may be unexpected issues with this approach given all of the variables that could affect this.

Evaluation

| Pros | Cons |

|---|---|

| No/Low Additional Complexity | Limited to Radius Search |

| Tiny Timeline | Non-performant with a large customer_addresses table |

| Easily replaceable | Doesn’t add additional capabilities for future features |

| “Buys time” to implement the “right” solution” | |

| No/Low Cost |

Solution 2: Scooby Doo

As our startup grows, so too must our product. We may push off this solution as long as we can until there is true demand for better geographic accuracy than a simple radius search can give us. For example, let’s say you are a software engineer for a logistics broker. There’s now a high value in showing which destination facilities fall outside of a given region (in this example, we will use the state of Colorado) for invoicing reasons.

For this, we will use a GIS database extension - PostGIS.

Step 1: Installation

Installation is dirt simple. If you are running Postgres in a cloud environment, the likelihood is you already technically have the extension installed - it just needs to be enabled.

If you are NOT running it in a cloud environment, then just run brew install postgis or the Linux/Windows equivalent(s) to install the extension

To enable PostGIS, simple connect to the database with your postgres user and run:

CREATE EXTENSION postgis;

Step 2: Load the data

We can actually use the load the same shapefiles into PostGIS to generate tables for each layer that we’d need.

Using ogr2ogr we can do:

ogr2ogr -f "PostgreSQL" \

PG:"dbname='{database_name}'\

host='{database_host}'\

port='{database_port}'\

user='{database_username}'\

password='{database_password}'" \

{shapefile_path} \

-nln {database_table_name} \

-s_srs EPSG:4326 \

-t_srs EPSG:4326

Be sure to replace {database_name}, {database_host}, {database_port}, {database_username}, {database_password}, {database_table_name}, and {shapefile_path} with the corresponding values.

Command breakdown:

ogr2ogr: Command to convert simple features data between file formats.-f: Determines the output format. In this case, “PostgreSQL”PG:"…": Defines connection parameters for the CLI to use. This command will run the queries to load the data so you’ll need credentials with privileges to do so.-nln: Allows you to define a table name for this data.-s_srs: Source Spatial Reference System (SRS). Not super useful unless you already know what you’re doing which isn’t really the target audience here. You can read more about SRS here.-t_srs: Transform SRS - you can transform the data into a different SRS if you happen to need it.

After running this command, you should now have a table in the database with the name that you defined. Congratulations! You’ve loaded a shapefile into Postgres! 🎉

Step 3: Proximity Search

Okay now that we have our shapefile(s) loaded, let’s actually do this thing!

Going back to the original ask, we are looking for facilities within approximately x miles of Colorado. Now how do we do this? Well in the end, each region is just a polygon so some arithmetic should assist us. We can take the shape of the polygon and “resize it whilst keeping the aspect ratio” (think shift+click+drag the corner of a picture) and then search within that resized shape. Luckily, there’s [a PostGIS function] for that!

Visualization:

The ST_Buffer function is exactly what we’re looking for.

Definition from postgis.net:

Computes a POLYGON or MULTIPOLYGON that represents all points whose distance from a geometry/geography is less than or equal to a given distance.

So we can utilize this to give us the following query:

SELECT facilities.*

FROM facilities, {database_table_name}

WHERE ST_Contains(

ST_Buffer({database_table_name}.geom, {distance_in_meters}),

ST_POINT(facilities.latitude, facilities.longitude)

)

There you have it - a buffered search in PostGIS.

Step 4: Optimization (Optional)

While technically optional, this section is highly recommended due to easily fixable performance concerns with the query above. First off, indexes!

Spatial Indexes

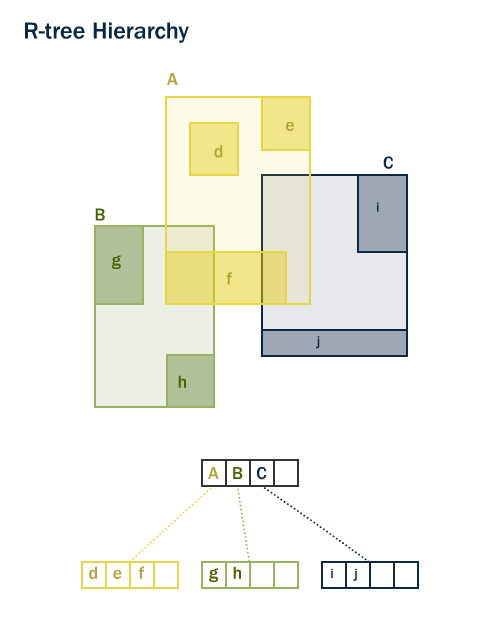

In order to take full advantage of PostGIS, we really need to index the facilities table. This will allow us to tailor in our results to just the bits we care about. There’s a ton to read about spatial indexes, but for the sake of keeping this short (😅) I’ll just do a quick summary:

Spatial indexes are ways of organizing spatial data in a traversable tree-type structure for faster searching.

Visualization:

From postgis.net

From postgis.net

Unfortunately, ogr2ogr doesn’t automatically add indexes to the shapefile-generated tables so we’ll have to add one ourselves.

CREATE INDEX {database_table_name}_geom_idx

ON {database_table_name}

USING GIST (geom);

That should speed up the querying for our state geometries but we now need to make sure our facilities are also indexed. As seen above, we already store latitude and longitude in separate columns. We convert lat/long to a geometry at query runtime. If we want to optimize further (we do), we should add a spatially indexed column to the facilities table.

PostGIS ships with a function to do add the column.

SELECT AddGeometryColumn ('{database_name}','facilities','geom',4326,'POINT',2);

Now we need an index:

CREATE INDEX facilities_geom_idx

ON facilities

USING GIST (geom);

Great! But how will we populate this column with data now? I’d suggest a trigger function like the following:

CREATE OR REPLACE FUNCTION update_geometries()

RETURNS TRIGGER

LANGUAGE plpgsql

AS $$

BEGIN

NEW.geom = st_setsrid(st_point(NEW.longitude, NEW.latitude), 4326);

RETURN NEW;

END;

$$;

And apply it to the facilities table

CREATE TRIGGER

tr_facilities_updategeom

BEFORE INSERT OR UPDATE of latitude,longitude on

facilities_updategeom

FOR EACH ROW EXECUTE PROCEDURE update_geometries();

With these optimizations in place, we can also simplify the query a bit:

SELECT facilities.*

FROM facilities, {database_table_name}

WHERE ST_Contains(

ST_Buffer({database_table_name}.geom, {distance_in_meters}),

facilities.geom

)

And it should run MUCH faster.

Simplifying Polygons

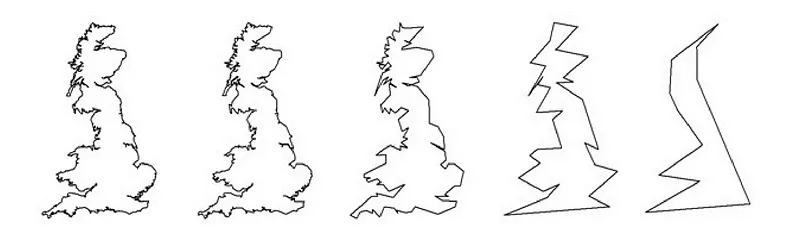

Colorado is rectangular right? Wrong! There are hundreds of vertices on the Colorado border. The amount of vertices is directly correlated with the latency of calculating a buffer for a given region so sometimes it’s worth it to simplify the polygon before calculating the buffer with a (nominal) trade-off of accuracy.

Visualization:

Each state is likely to have a different level of simplification based on the amount of vertices but since it’s relatively static, you can create a simplified_geom and just load that version in individually. As we get narrower and narrower (i.e. county, city, etc.), that becomes less feasible to do manually. I’d suggest finding a single method of simplification understanding that there will be some sort of distribution where the accuracy may be higher than others.

How do we simplify geometry though? Are you picking up the pattern yet? There’s a function for that.

ST_Simplify (docs) takes a geometry and a tolerance (in meters) and applies the Douglas-Peucker algorithm on the edge of the polygon. You might want to tune this tolerance value a bit to your liking to balance accuracy and performance. General guidance from me is somewhere between 1km and 10km for states but the ultimate value will be determined by your requirements.

Now that we’ve added some performance optimizations to our proximity search, we should evaluate this approach compared to the radius search.

Estimate

Time estimate: 2-4 weeks

The extra variance here is mainly due to testing and optimization. It’s not a huge difference but it’s worth taking into account considering the business priorities.

Evaluation

| Pros | Cons |

|---|---|

| Allows for quick iteration on new GIS features | Additional complexity |

| More performant than Radius Search (with optimization) | Requires more maintenance |

| More flexibility | Much larger storage requirements |

| Higher accuracy | |

| Low Cost |

Alternatives

What? You thought it was over? Of course there are other ways to go about this!

- Bounding Box Only Search: Simpler than Solution 1, this is an overlay style search that would use the “radius” as a lat/lng adjustment. This is a good idea if you can sacrifice accuracy for performance since this is an easily optimized query:

SELECT * FROM customer_addresses WHERE latitude BETWEEN (centroid_latitude + radius) AND (centroid_latitude - radius) AND longitude BETWEEN (centroid_longitude + radius) AND (centroid_longitude - radius) - PostGIS Anyway: PostGIS is more than capable of calculating centroids on the fly as well as managing your Haversine/Radius/Bounding Box searches in great time! Please take it into account if the benefits outweigh the additional complexity costs.

- Third Party Services: In many cases, I prefer to build over buy because there’s often a desire for new or improved features on top of it. That said, this specific instance is the perfect “buy” decision. Geocoder.ca has very affordable pricing options for the growing startup that needs something quick. A sprint’s worth of work for one engineer is more expensive than this service. The drawbacks (of course) are that it’s not as easy to build off of.

- Others? If you have any other suggestions for solving this problem, feel free to reach out at my email on my GitHub.

Conclusion

Proximity Searching is a fun, non-trivial problem that, as presented above, can be solved in a plethora of ways.

If you like my writing style, presentation, and/or solutions, please consider sharing this with a friend!

Check out my less serious writing over here!